Briefing: Myanmar’s new industrial zone law

July 2020

More Paper Shuffling Than Progress?

New industrial zone law could be a case of one step forward, two steps backward if not properly implemented

Note – As of writing the official transcript of the law was in Myanmar language only but an unofficial English language translation was provided in the public domain by Lincoln Legal Services (Myanmar) Limited. All comments are based on this translation.

The Industrial Zone Law was enacted in May 2020 in order to revamp the operations and regulatory procedures of existing, as well as future, industrial estates in Myanmar. Long forgotten during its decades of economic isolation, a period when many of its neighbours moved from rags towards riches through rapid industrialisation, Myanmar has now started to begin catching up.

However, the country has a long way to go to emulate Korea, Thailand and even Vietnam, with significant investments required to upgrade decrepit infrastructure and build bigger and better industrial estates or find a way to improve the existing poorly planned and executed parks estates that are beset by a myriad of issues, chiefly inefficiency.

Improvements to Myanmar’s industrial sector is more essential given the rapidly changing global socioeconomic landscape the country finds itself in – a global pandemic that presents enormous threats to further growth but also opportunities for a country like Myanmar that enjoys a unique geographic location between two of the world’s economic powerhouses.

Myanmar’s Industrial Zone Law was introduced in the middle of the Coronavirus storm that is ravaging the world economy. However, a post COVID-19 world is certain to be very different to the one we knew prior to the declaration of the pandemic.

Manufacturing and supply chain trends may be accelerated or perhaps blown off course. The gradual pivoting away from the Chinese manufacturing powerhouse, due to increasing labour costs, may force a hasty rethink of the China Plus One policy many companies have adopted since the early 1990s.

The abrupt closing of international borders, as well as global dissatisfaction with China’s handling of the outbreak, have raised supply dependence concerns and political/trade rifts that would benefit its neighbours, including Myanmar, which are clamoring for business and in many ways well placed to benefit. On the other hand, key markets in Europe and North America are starting to bring manufacturing back to their shores supported by the rapid improvement in automation, tariff issues and political pressure to boost job markets “back home” – typically wealthy Western economies and Japan that profited most from offshoring manufacturing work to China.

Industrial estates globally have provided the bedrock for economic growth ever since the first industrial estate: Trafford Park in Manchester, England, which was set up at the end of the 18th century. Generally, the industrial zone sector in Myanmar is one of neglect, poor management, limited infrastructure and ill-defined ownership.

The Industrial Zone Law that was passed in May 2020 aims to address the myriad but sadly the legislation does little to tackle the core issues and could even be a significant step backwards for industrialization.

But setbacks are nothing new to Myanmar.

A turbulent industrial legacy

The existing industrial estate structure started with the transition to a market economy in 1988, which began the process of more efficient privately-led manufacturing for local consumption. With the development of a garment-for-export sector in the 1990s state-owned and managed industrial estates started to spring up. But they lacked the basic infrastructure that was becoming standard in other developing industrial economies, such as Thailand and Indonesia. Then double barrel disaster: the Asian Financial Crisis hit in 1997 and then a few short years later Western trade regulations and sanctions in the early 2000s, which mostly shut the doors for exports to the USA and Europe. These two markets accounted for up to 90% of garment exports. Myanmar’s industrial development stagnated along with the industrial estates that supported it.

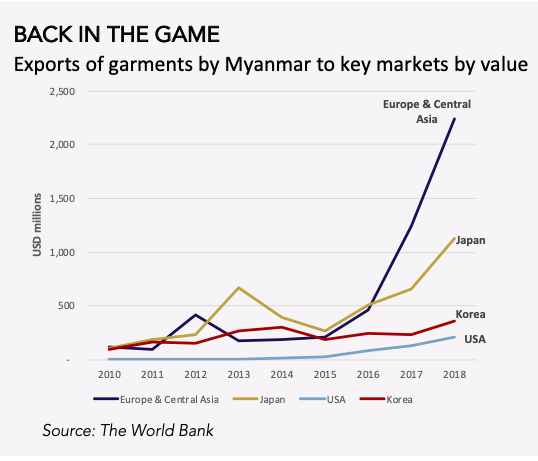

Garment and footwear exports started to expand again at the end of the 2000s to serve growing Japanese and Korean demand, but it was the ending of sanctions and introduction of low or zero tariffs to key markets in Europe and the USA following political reforms post-2011 that led to a resurgence of production.

Significant foreign investment entered not only to build export manufacturing but also to boost food and beverage production for domestic consumption, a move with the potential to develop a strong value-added food export industry based on Myanmar’s promising agricultural future. Other industries have begun tentative steps into the country such as electronics and automotive sectors.

But where to establish all of this manufacturing? Existing industrial estates became the focus of attention, especially Hlaing Tharyar in west Yangon, with its large land area and abundance of willing workers boosted by migration from the Ayeyarwady delta after Cyclone Nargis in 2008. Despite the limitations of most of the industrial zones occupancy has surged in the past six years but many would-be investors have been put off, partly as result of substandard facilities and opaque land ownership.

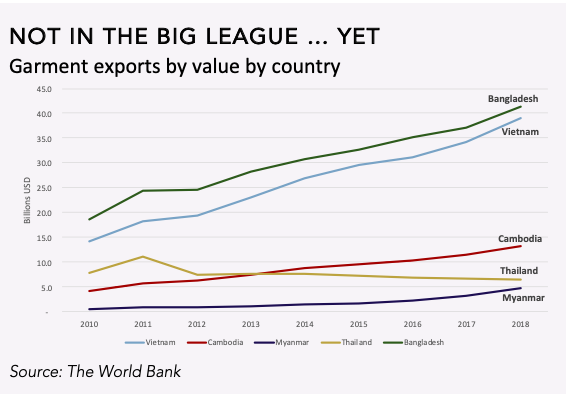

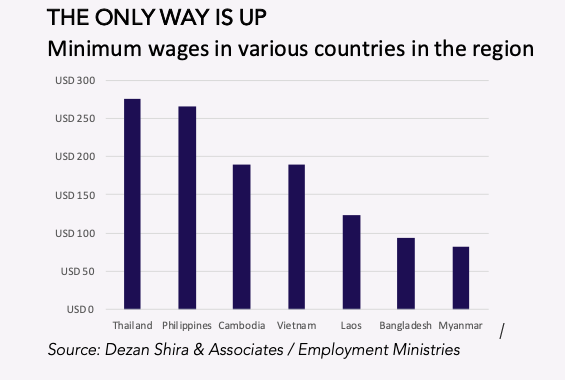

Myanmar is at the bottom of the ladder for industrial development, exactly where every country started its industrialization. Low value-added sectors still employ significant numbers of people, often supporting families in poorer areas of the country and helping to reduced poverty levels. The garment export sector, however, still remains in its infancy compared to rivals Vietnam and Bangladesh as the key suppliers outside of China. Productivity is low by international standards. Food and beverages, representing the largest industry sector in the country, almost exclusively caters to the growing domestic market due to low quality standards in both manufacturing and agriculture.

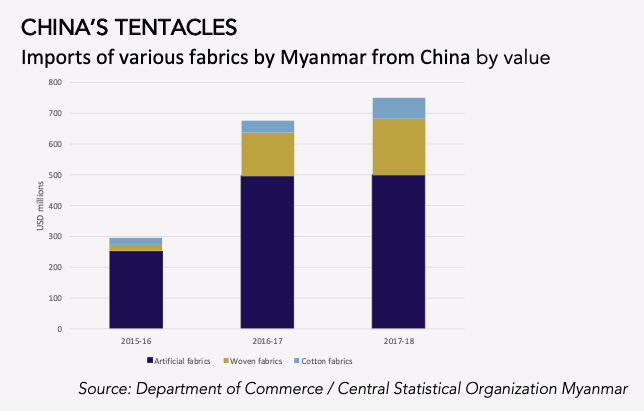

Myanmar’s input trap

The Cut-Make-Pack (CMP) process dominates the garment sector in Myanmar. This production method requires low startup costs but also adds little value to Myanmar beyond wages for workers. Nearly all production inputs – textiles, accessories and even packaging that is essential for the production of export-destined garments – are imported, mainly from China. While the low investment threshold makes CMP an attractive option for CMP producers, and generates hundreds of thousands of jobs for low wage workers, it adds little to Myanmar’s tax office and – as we can see – is vulnerable to external shocks.

The initial COVID-19 shock was a supply led one where China’s drastic lockdown led to severe disruptions in inputs, where factories were unable to input the raw materials they required for production. Sadly, the initial slump was quickly overtaken by an even trickier one: cancelled orders, as buyers withdrew orders as lockdown measures hit home in key markets.

The move from CMP to Free-on-Board (FOB), where one country captures the lion’s share of the manufacturing process, allows for more control as well as greater economic benefits. An innovative industrial policy focused on developing higher grade domestic textiles and garment accessories would go some way to moving the country up the value-added ladder and lessening dependence on outside suppliers. Evolving environmental trends such as circular manufacturing, including the use of eco-friendly fibres and other products, could be seized on to leverage Myanmar’s enormous agricultural potential. A number of factors hamper progress, namely intermittent electricity, poor transport infrastructure, labour skills and limited financial capacity but professionally managed industrial zones could go some way to address these problems.

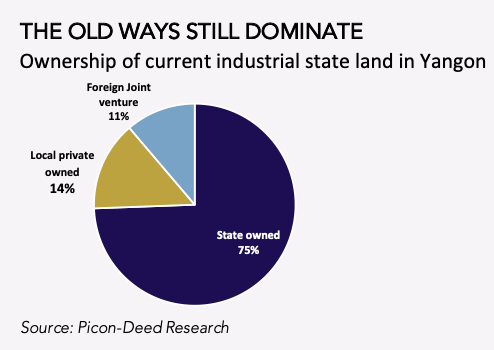

Most industrial estate land in Myanmar is state owned and managed and are generally beset by issues of poor internal road systems, limited electricity, no wastewater treatment, and a lack of clarity over land ownership where such land is subject to bouts of speculation during hot property market periods. The government recognizes the problems, but so far only halfhearted attempts have been made the remedy the situation. Over the past decade the government has made many statements that it will tackle land speculation in industrial estates but these have yielded no tangible results.

There is also no requirement that the government build industrial estates itself: within the region there are many excellent companies with established track records of building quality parks. With the right incentive it would be possible to encourage these companies to come and do business in Myanmar.

Current and future silver linings

There have been some positive exceptions to the overall landscape. A Japanese (now Singaporean)/local joint venture international-grade industrial estate was set up close to the airport in 1998 – the Mingalardon Industrial Park. The next – and far larger – new international standard industrial estate was introduced in 2015. The Thilawa Special Economic Zone was to be the first of three Special Economic Zones (SEZs) to start operation, the others being Dawei (Tanintharyi Region) and Kyaukpyu (Rakhine State), which are in various stages of planning. All three SEZs are close to seaports and also have a Special Economic Zone law to regulate them. Currently Thilawa SEZ, to the south-east of Yangon, has developed about 1,440 acres out of nearly 5,000 acres.

Other plans for new privately managed industrial zones have fallen by the wayside, hampered by slow approval processes and master planning that incorporated excessive space for non-core real estate: retail, office and residential. One thing the new law gets correct is rightly limiting commercial use to 1-5% of the total development.

One project that is moving ahead is the Yangon Amata Smart and Eco City, which is being developed by Amata Corporation, a specialist Thai industrial estate developer. Covering 800 hectares in eastern Yangon, the project is set to begin construction this year.

Another more nebulous venture is New Yangon City to the west of the city, which is slated to include 20 square kilometres of industrial zone or about one-quarter of the overall development which will include significant residential and commercial uses. Currently the project is mired in various controversies included but not limited to potential flooding, a previously sanctioned Chinese partner and neglect for the development of existing Yangon.

While new, well managed industrial zones would be required over the coming decades to support growth, there is an urgent need upgrade of the nearly-13,000 acres of existing industrial zone land that does not meet international standards. This is one key area that the new law sadly only pays lip service to. In fact, one article in the law specifies that manufacturers in existing industrial zones would be responsible for the disposal of waste products themselves in these zones which, exemplifies a defeatist attitude.

The fact that the law has been drafted during the COVID-19 crisis is in itself encouraging and highlights the need to revamp Myanmar’s industrial base. The overall objectives are to further develop industrial zones throughout the country with an emphasis on poorer geographical areas and to create employment opportunities. The law acknowledges the need for improving social and environmental safeguards as well as the use of industrial land for the intended purpose – and for which permission was granted – rather than speculation. Little in the past has been done to remedy this, with the possible exceptions of Mingalardon and the Thilawa SEZ; both examples where a strong developer has kept the development in order.

However laudable the aims are of any law; it is in the people and implementation that serves as the basis on whether a law succeeds or fails in its objectives. There are strong concerns as to whether this is probable under the current provisions. Sadly, the law overemphasis the extensive use of amorphous committee structures that are likely to impede rather than invigorate.

A new Bumbledom

The law proposes the overall control be vested in a Central Committee. The provisions are not clear on who actually is responsible for the appointments. In other regional industrial estate laws selection of key members are often vested in the cabinet and some provisions are made for the technical abilities required for the positions. In Bangladesh, which has seen rapid industrial development, the committee of the Bangladesh Special Economic Zone Authority (BEZA) has specific appointees from the central bank, the board of investment and chamber of commerce, for example. In Myanmar the law only specifies that representatives shall be from appropriate persons from various ministries.

One glaring omission are any provisions for the management of the structure that will regulate and promote the development of industrial zones in the country. In fact, the law does not even provide a specific name for the authority such as BEZA in Bangladesh or the Industrial Estate Authority of Thailand (IEAT). In Thailand the law specifies a governor as being responsible full-time for the running of the IEAT and a management committee to oversee its operations. Most industrial authorities use a board that oversees strategy and a full-time management team for the day-to-day operations. It is difficult to see any authority being effective in Myanmar without a similar structure and full-time dedicated staff for what should be seen as a critical step in Myanmar’s development.

The law also focuses significant attention on Regional Committees, which would seem to be responsible for most of the activities in the law. Thailand has 56 industrial estates that have been developed since the setting up of IEAT nearly 50 years ago and has no need for regional committees. Other regional authorities are also run as one national body with only branch offices to support some administration and marketing. The number of new industrial estates expected to be developed or redeveloped in Myanmar over the next 30 years will be small, perhaps totalling around 20. This surely would not be too much burden for a well-organized national body to undertake, especially as industrial policy should be national in focus. Plenty of other regional authorities and organizations are able to represent the states and regions in submitting proposals for new industrial estates as well as consultation on local matters. Such bodies include state and regional authorities, local DICA offices, local chambers of commerce and NGOs. The addition of a significant number of regional committees seems to be a highly bureaucratic endeavour.

On top of a Central Committee, Regional Committees and Sub-Committees; the law also adds yet another layer of bureaucracy – the so-called Management Committees. Given that the current poorly run state industrial estates are already run by committees this does not create much confidence that any real progress will be made. It has also not been specified if the focus of existing and future industrial zones will be more towards privately owned or joint venture managed operations or those run by the state. Generally, privately run industrial estates are more successful and even nominally socialist countries like China and Laos have preferred this model.

In the event of private industrial estates, a management committee would appear unnecessary and create a level of micromanagement – perhaps even interference – that would be unattractive to industrial estate developers that might rightly point out that they have more experience in the field. A far more efficient process would be direct liaison between each industrial estate and a professionally run central authority responsible for creating and administering regulations but also provide positive incentives that can be offered as and when required.

There would seem scant opportunity under the new law to allow the Central Committee to have any form of regulatory override cutting through the statutory provisions from national level ministries such as customs, income tax, land issues. The composition of the committees, based on ministry representatives, is unlikely to alter this dynamic. A more ambitious law would allow for a combination of some exemptions from existing laws such as tax incentives as well as streamlined procedures such as a one-stop shop allowed in the Thilawa SEZ. The ability to fast track electricity power plants would be of enormous advantage and indeed critical for some zones. Sadly, the plethora of committees mentioned in the law makes proactive decision making inconceivable.

In all probability, the various committees – lacking proactive powers – are most likely to stress more negative regulatory aspects, which will in turn lead to unnecessary delays in approval processes. The law presently reinforces the concerns stated in a recent IFC Report “Creating Markets in Myanmar”, which states that the country is “still burdened by red tape and lengthy process that can be linked to controlling transactions rather than facilitating firm’s growth”.

Industrial estate policy has often been the spearhead for much further reaching economic reforms. The obvious case is China where the special economic zone in the Shenzhen was the first experiment of market forces in a previously strictly socialist and poverty-stricken economy. Rather than the timid, bureaucracy-laden law that does nothing to address the opportunities and challenges of the 21st century, Myanmar needs a far more ambitious law that will allow the country to be an effective player in the new, dynamic industrial landscape the world faces.

Taking on the 21st Century

Industrial estate policy and implementation requires just one strong national decision-making authority (with a name!) backed up by a full-time professional management team. BEZA has around 120 full time staff. This authority should have wider remit to allow for some extra powers to incentivize industrial development, such as tax exemptions, for particular industries. Going further, incentives could also be provided to producers moving up the value chain such as FOB in garments as well as compliance to specific international standards in the fields of safety, quality and environment. Again, there are regional examples to follow here: China has gradually shifted its incentives and tax breaks to areas further within its borders and away from the coast to bring jobs and skills to those areas. Tougher powers should also allow the authority to impose sanctions on speculators in state-owned industrial zones.

Classification of industrial estates into two or three categories based on various criteria such as waste treatment, internal road system is also recommended with incentives for higher categories to encourage the upgrading of existing industrial estates. To support this further, the authority should draw up a feasibility study and corresponding action plan for revamping existing industrial estates to international standards.

This need not drain government coffers. A grading system complete with incentives would encourage developers to continually invest in the maintenance and upgrading of facilities or risk losing their tenants. In the long run this will benefit the economy as a whole and bring in more revenue to support the state.

A dynamic authority would also constantly be acquiring information about the rapidly changing industrial scene, passing information on to developers and the government to fine tune incentives and regulations. A proactive authority could also take part in trade shows all over the region to promote the industrial zones. The authority could also regulate and support training centre standards so that training matches the needs of more sophisticated manufacturing processes, which would improve the chances of Myanmar climbing up the value-added chain, improve skill levels and boost incomes, just as regional economies have so successfully done.

Before 2020, tectonic changes have been taking place in the manufacturing sector with advances in technologies, trade rifts, environmental and social concerns by consumers as well as a shift away from China. And then came COVID-19, which may have accelerated these changes. Effective industrial policy in the 21st century needs knowledge, dynamism and the power to make positive changes in order to adapt and prosper in the new economic reality. The proposed bureaucratic smorgasbord of ill-defined, toothless committees will likely fail to achieve this and may even result in a few steps backwards.

Time to think again.

Contact email: picondeed@gmail.com

Website: www.picondeed.com

Real Estate Courses at Udemy – Take a look here